The Cancer Research

Cranberries provide a modest amount of vitamin C, but the main source of cranberries’ potential for cancer prevention comes from their package of phenolic compounds. These include polyphenols, found in most berries, as well as a relatively unique type of proanthocyanidin. Because many of these compounds are complex molecules broken down by gut microbes, there is potential for broad effects on the gut microbiota and inflammation. Individual differences in gut microbes could mean that people differ in cancer protection from cranberries.

Interpreting the data

After a systematic review of the global scientific literature, AICR/WCRF analyzed how fruits and their nutrients affect the risk of developing cancer.

“Convincing” or “probable” evidence means there is strong research showing a causal relationship to cancer—either decreasing or increasing the risk. The research must include quality human studies that meet specific criteria and biological explanations for the findings.

A convincing or probable judgement is strong enough to justify recommendations.

- There is probable evidence that non-starchy vegetables and fruit combined DECREASE the risk of:

- Aerodigestive cancers overall (such as mouth, pharynx and larynx; esophageal; lung; stomach and colorectal cancers)

“Limited suggestive” evidence means results are generally consistent in overall conclusions, but it’s rarely strong enough to justify recommendations to reduce risk of cancer.

- Limited evidence suggests that fruit may DECREASE the risk of:

- Lung cancer (in people who smoke or used to smoke tobacco) and squamous cell esophageal cancer

- Limited evidence suggests that non-starchy vegetables and fruit combined may DECREASE the risk of:

- Bladder cancer

Ongoing Areas of Investigation

- Laboratory Research

Tannins such as proanthocyanidins are complex compounds that are mostly unabsorbed from the digestive tract. Some researchers consider these likely to be the cranberry phytocompounds most protective against cancer.

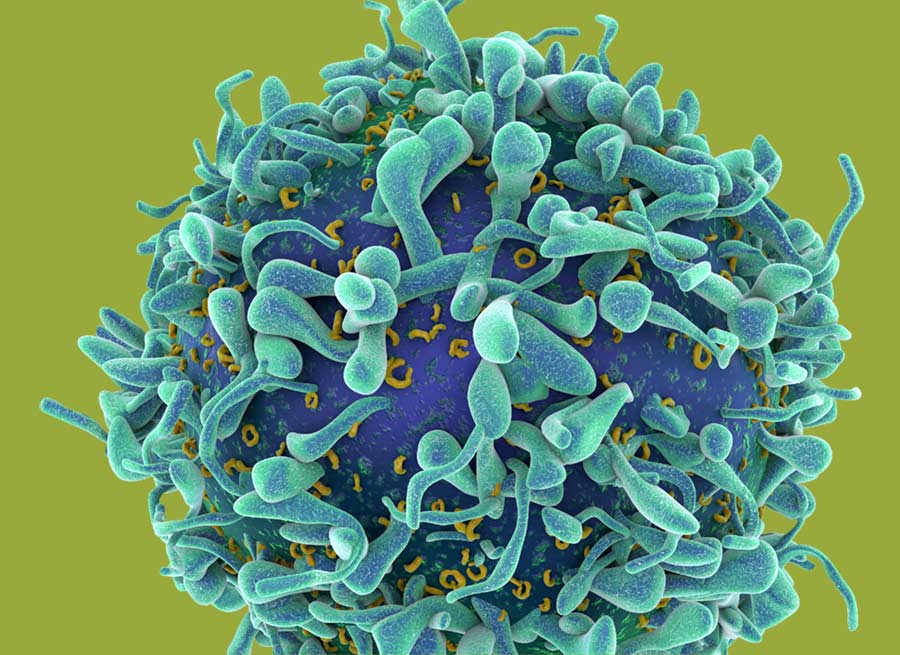

In cell studies, proanthocyanidins are antioxidants that seem to influence gene expression to decrease growth of cancer cells and increase their self-destruction. However, this may not reflect what occurs when they are consumed in food, especially in cells outside of the gut. Microbes in the gut break them down to form other phytochemicals that might have anti-inflammatory effects throughout the body.

Anthocyanins influence cell signaling in ways that increase antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and carcinogen-deactivating enzymes in cell and animal studies. They inhibit cancer cells’ growth and ability to spread, and activate signaling that leads to self-destruction of abnormal cells.

Phenolic acids show potential to increase cells’ antioxidant and anti-inflammatory defenses against damage that could lead to cancer, based on cell and animal studies. Emerging evidence in animal studies suggests they may also improve glucose metabolism and decrease insulin resistance, and alter the gut microbiota (microbes living in the digestive tract), creating an environment in the body less likely to support cancer.

Triterpenoids (such as ursolic acid) can increase antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and carcinogen deactivating enzymes by influencing cell signaling pathways and gene expression in cell studies. They also decrease growth and increase self-destruction of isolated cancer cells.

Cranberries, provided in limited animal studies as freeze-dried fruit, powders, extracts or purified compounds, can increase antioxidant enzyme activity, decrease oxidative stress and reduce inflammation and tumor incidence in the colon. These cranberry products inhibit a variety of different types of cancer in animal models.

Laboratory studies need to be interpreted with caution, partly because they may use phytochemicals in concentrations far beyond levels that would circulate in the body. Also, the bioavailability and activity of phytocompounds like those in cranberries depends not only on what’s in the fruit, but also on how they are broken down by the gut microbiota, taken up into the blood and circulated through the body.

- Human Studies

Human studies related to cranberries and cancer risk mainly compare groups of people who consume relatively high and low amounts of total fruit or berries; few human studies address cranberry consumption specifically.

People who eat more fruits have lower risk of a wide range of cancers. This probably reflects combined protection from many different nutrients and compounds they contain.

Flavonoids: People whose diets were higher in anthocyanins had lower levels of markers of inflammation, and those with diets higher in flavonols showed lower levels of oxidative stress, in cross-sectional analysis of a large population study.

One short-term study of a small group of healthy older adults found that cranberry phytocompounds were absorbed and antioxidant defense capacity increased for several hours following consumption of cranberry juice.

- AICR-Supported Studies

Featured Studies

- Tips for Selection, Storage and Preparation

Selection:

- Whole fresh or frozen cranberries provide larger amounts of phytocompounds than other forms.

- Choose cranberries that are firm and not shriveled.

- Commercial cranberry juice and sauce also contribute noteworthy amounts of cranberry phytocompounds, although amounts of many are reduced by at least half by heat and removal of skin and seeds during processing. Because of cranberries’ tart taste, most juice is sold sweetened or as part of a blend with other fruit juices. In each 6-ounce glass, sugar content is like that of apple or pineapple juice with one extra teaspoon of sugar added.

- Dried cranberries offer almost no vitamin C, but they do provide some phytocompounds, including ursolic acid and proanthocyanidins.

Storage:

- Unlike most other berries, you can refrigerate cranberries for up to two months.

- For longer storage, freeze cranberries in the bags in which you purchased them. Or wash, dry and freeze in a single layer on a cookie sheet; then store in an airtight container or freezer bag for nearly a year.

- Store dried cranberries in an airtight container at room temperature for up to three months; check expiration date on packaged berries.

Preparation Ideas:

- Add dried cranberries to cereal, oatmeal or plain yogurt.

- Balance fresh cranberries’ tartness by mixing with other fruits, such as oranges, apples and pears for a relish or salsa.

- Experiment with cranberries added to rice or whole-wheat stuffing.

- Try fresh or dried cranberries as a colorful addition to a green or carrot salad.

- Enjoy the flavor contrasts by combining dried cranberries with vegetables like Brussels sprouts or with apples and red cabbage over pork.

- Add fresh, frozen or dried cranberries to muffins and quick breads. Do not thaw frozen cranberries before adding them to the batter.

- Mix dried cranberries with nuts and other dried fruit to make trail mix.

- Add cranberries to baked apples or apple crisp.

From the Blog

References

- Prasain JK, Grubbs C, Barnes S. Cranberry anti-cancer compounds and their uptake and metabolism: An updated review. Journal of Berry Research. 2020;10:1-10.

- Weh KM, Clarke J, Kresty LA. Cranberries and Cancer: An Update of Preclinical Studies Evaluating the Cancer Inhibitory Potential of Cranberry and Cranberry Derived Constituents. Antioxidants. 2016;5(3):27.

- Smeriglio A, Barreca D, Bellocco E, Trombetta D. Proanthocyanidins and hydrolysable tannins: occurrence, dietary intake and pharmacological effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174(11):1244-1262.

- Montgomery M, Srinivasan A. Epigenetic Gene Regulation by Dietary Compounds in Cancer Prevention. Advances in Nutrition. 2019;10(6):1012-1028.

- Duthie SJ. Berry phytochemicals, genomic stability and cancer: Evidence for chemoprotection at several stages in the carcinogenic process. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(6):665-674.

- de Sousa Moraes LF, Sun X, Peluzio MdCG, Zhu M-J. Anthocyanins/anthocyanidins and colorectal cancer: What is behind the scenes? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(1):59-71.

- Del Rio D, Rodriguez-Mateos A, Spencer JP, Tognolini M, Borges G, Crozier A. Dietary (poly)phenolics in human health: structures, bioavailability, and evidence of protective effects against chronic diseases. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(14):1818-1892.

- Tajik N, Tajik M, Mack I, Enck P. The potential effects of chlorogenic acid, the main phenolic components in coffee, on health: a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur J Nutr. 2017;56(7):2215-2244.

- Villa-Rodriguez JA, Ifie I, Gonzalez-Aguilar GA, Roopchand DE. The Gastrointestinal Tract as Prime Site for Cardiometabolic Protection by Dietary Polyphenols. Advances in Nutrition. 2019;10(6):999-1011.

- Li W, Guo Y, Zhang C, et al. Dietary Phytochemicals and Cancer Chemoprevention: A Perspective on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Epigenetics. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29(12):2071-2095.

- Afrin S, Giampieri F, Gasparrini M, et al. Chemopreventive and Therapeutic Effects of Edible Berries: A Focus on Colon Cancer Prevention and Treatment. Molecules. 2016;21(2):169.

- World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Wholegrains, vegetables and fruit and the risk of cancer. Available at: dietandcancerreport.org.

- Aune D. Plant Foods, Antioxidant Biomarkers, and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality: A Review of the Evidence. Advances in Nutrition. 2019;10(Supplement_4):S404-S421.

- Cassidy A, Rogers G, Peterson JJ, Dwyer JT, Lin H, Jacques PF. Higher dietary anthocyanin and flavonol intakes are associated with anti-inflammatory effects in a population of US adults1. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(1):172-181.

- McKay DL, Chen CYO, Zampariello CA, Blumberg JB. Flavonoids and phenolic acids from cranberry juice are bioavailable and bioactive in healthy older adults. Food Chemistry. 2015;168:233-240.

- Blumberg JB, Camesano TA, Cassidy A, et al. Cranberries and Their Bioactive Constituents in Human Health. Advances in Nutrition. 2013;4(6):618-632.

- Vinson JA, Bose P, Proch J, Al Kharrat H, Samman N. Cranberries and cranberry products: powerful in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo sources of antioxidants. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(14):5884-5891.