Americans have been trying to make sense of food, nutrition and what a healthy diet is for at least 100 years. And throughout, health professionals (and others) have given advice liberally. How has that advice changed?

Americans have been trying to make sense of food, nutrition and what a healthy diet is for at least 100 years. And throughout, health professionals (and others) have given advice liberally. How has that advice changed?

Certainly, we know much more about diet and cancer prevention. Even just 30 years ago most people did not believe the idea that what we eat would affect our risk for cancer. But now AICR has specific, evidence-based recommendations for cancer prevention.

We also have more powerful information and evidence for how foods and nutrients affect our health in other ways, both short-term and long-term. We understand how to treat diseases related to diet much better – like celiac disease and diabetes. We also know more about nutrition in illness recovery. And as we learn more about genomics, metabolomics and other omics, we can address individual needs and improve personalized diets for disease prevention.

Yet, even with all the research and new discoveries, we still struggle with helping people take nutrition knowledge and put it into practice on their plates. Today’s barriers to healthful eating include supersized and ever abundant overly processed foods. We advise getting back to basics – eating more vegetables, fruit, whole grains and legumes.

So what might we have seen for nutrition advice 100 years ago?

One book that may give us a glimpse, published in 1924 book, is called “Physical Culture Food Directory.” The author, Milo Hastings, was an American inventor, author, and nutritionist. He also invented a snack for children, called Weeniwinks, based on natural grains and no sugar. I don’t know how typical this book was for the time, but it’s interesting to see parallels to today’s popular nutrition books through his words.

On making nutrition more understandable:

“It has been my job to translate scientific facts and theories concerning human food and its relation to health and disease into a form…most understandable…and useful to the general public.” (A job description recognizable to the modern dietitian.)

“The need of simplifying this knowledge has grown greater because the knowledge…has grown more…complex and confusing.”

And Mr. Hastings reflects on some of the guidance provided by his peers of the time:

“It did no good to tell a man how many calories there are in a pound of potatoes, or how much protein in a pound of peanuts when he did not have any real comprehension of calories or protein nor know why or how much he should eat of either.”

“The human mind …is more impressed by a single idea with a lot of enthusiasm than …with complicated ideas that encompass the whole known truth.” (Think “Miracle Food”)

On how to personalize your diet:

On how to personalize your diet:

“The most helpful thing we can do is to work out a system of health food ratings that express health food values in terms that mean the most to the most people, and which they can follow without being lost in the mystic maze of technical terms and mathematical propositions.”

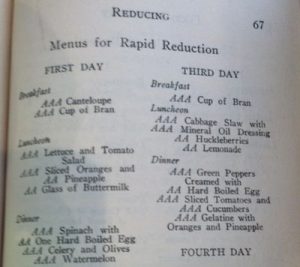

Mr. Hastings used his insights and the science of the time to develop a rating system for foods from “blank” (no value) to “AAA” (best for the purpose) for each of 5 purposes: Vitality, Growth, Reduction, Energy, Constipation. And although we would probably make a few changes to the specifics, the basic rating system had some sense.

Vegetables, fruit and whole grains rated highest to help with constipation, vitality and reduction.

Dairy products got more “A’s” for growth, vitality and energy, but blanks or just one A for constipation and reduction. Meat – A’s for growth and energy.

Sugars received blanks for everything except energy.

Under Coca-Cola and Coffee: Has no food value and contains caffeine a habit-forming drug.

On claims by food manufacturers:

In the chapter “Purity is Not Enough,” he discusses the fact that pure (as in white sugar and white flour) does not equal healthful.

“Purity in itself is not a guarantee of wholesomeness…Pure arsenic is a worse poison than impure arsenic. Cane sugar is about the purest food we have and about the worst.”

On who’s to blame for our unhealthful food supply:

Apparently some blamed the millers for the widespread use of white flour. But Hastings says, “they were merely trying to give the public what it wanted. The miller who had the whitest flour sold it at the best price….If the public would only use it (whole wheat flour) in large quantities the millers would actually make whole wheat flour.”

On giving practical advice and meeting people where they are:

On giving practical advice and meeting people where they are:

“It is as much our job to show a man who has got to live by eating at Boston restaurants how to select the best foods available for his needs, as it is to publish the story of a man living directly from the trees of a California fruit orchard.”

These quotes do seem familiar and some could be found in today’s popular diet books. We do face similar challenges as nutritionists faced 100 years ago because in giving nutrition advice and encouraging people to eat healthier, we are, after all, working with people. And people have likes and dislikes, beliefs and habits, cultural preferences and varying attitudes toward new things.

Our new knowledge, though, can help individuals find many ways to meet these goals. You can individualize the specific recommendations for your tastes, culture, health needs and goals. It’s apparently not completely new and not complicated – but it’s not always easy. However, it’s more important than ever because Americans are living longer and want to stay healthy.

You can start now to take simple steps to eat smarter and move move to lower your risk for cancer, type 2 diabetes and heart disease, a well as improve overall quality of life. Begin by beginning to change you plate to look more like AICR’s New American Plate.

Part 2 – 100 Years of Nutrition Advertising