A new paper offers guidance to researchers who are studying how following cancer prevention recommendations affect cancer risk and survival. The paper, just published in the journal Nutrients, proposes the first standardized scoring system for the AICR/WCRF Cancer Prevention Recommendations and was led by researchers at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), in collaboration with AICR/WCRF and researchers in Europe.

AICR/WCRF’s 10 Cancer Prevention Recommendations were updated in 2018 and are the culmination of a rigorous and exhaustive analysis of the decades of accumulated scientific evidence. They focus on how diet, physical activity, and body weight, as a combined package of lifestyle behaviors along with breastfeeding and other health-related choices, can lower the risk of cancers.

“The primary goal of the AICR/WCRF recommendations is to provide evidence-based advice to help people adopt a lifestyle that reduces their risk of cancer; their purpose was not for scoring people’s lifestyles. However, scoring overall lifestyles would enable direct quantitative comparisons of overall lifestyles,” said AICR’s Vice President of Research Nigel Brockton, PhD, who is also one of the paper’s authors.

A substantial body of independent research has shown that following the original 2007 Cancer Prevention Recommendations does lower cancer risk and helps survivors. We’ve written about some of those studies here.

These studies have generally used a point system; you get one point if you adhere to a recommendation and zero points if you do not. Some studies have given half a point for in-between. But what exactly does adherence or partial adherence to a recommendation actually mean? That depends upon how each study assigned their thresholds. In the past, each study has assigned their own thresholds for what constitutes adherence to each recommendation and that makes it challenging to compare and analyze the research.

“This standard scoring system is a practical tool which can be used to examine how adherence to the AICR/WCRF Cancer Prevention Recommendations relates to cancer risk and mortality in various adult populations. This means that adherence to the recommendations can be measured in different cohorts of people, from different parts of the world and allowing for greater consistency and comparability,” said WCRF International’s Susannah Brown, Head of Research Evidence and Interpretation and one of the paper’s authors.

The point system

In order to develop a simple and standard scoring system, the authors decided upon a three-level point system: 0, .5, and 1 depending upon the degree to which someone follows a recommendation. The paper focused on eight of the ten recommendations. They did not include the recommendation to avoid dietary supplements and the one for cancer survivors, as those were covered inside other recommendations. The recommendation on breastfeeding is optional.

Authors first looked at the quantitative values stated in the supporting goals that accompany the AICR/WCRF Cancer Prevention Recommendations. When specific cut-points were not stated, they reviewed guidelines from other leading health organizations, including the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Physical Activity Guidelines.

A couple of the recommendations were allotted two sections, each worth half a point at the most. AICR’s first recommendation to stay a healthy weight, for example, is broken into a BMI and waist size category. Having a healthy BMI will give you half a point; a healthy waist circumference adds another half point. If data is only available for one of these sections then the section score is doubled.

The collaborative approach between NCI and AICR/WCRF allowed for discussion and clarification when areas were ambiguous. Standardizing the recommendation to “limit fast-foods and processed foods high in sugars, fats and starches” was especially challenging as there was no previous standard by which to categorize or define cut-points, said NCI’s Jill Reedy, PhD, RD, Program Director in the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences and the paper’s senior author. At the end of the process, researchers developed three groups of processed food intake after adapting food categories according to an accepted classification tool called NOVA (not an acronym).

Setting a global standard

It was important that the standards apply to the variety of tools that researchers use to collect dietary data, such as food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour recalls, and in different countries. There is a real need for more global research, comparing associations by ethnicity, genetic ancestry and geographical region.

“Most of the research on cancer risk associated with these factors (diet, physical activity and obesity) have been conducted in Western/high income countries,” said Brockton. “There are significant differences in both exposures and biology between populations. For example, Asian populations will exhibit detrimental metabolic changes at a lower BMI than those of predominantly European descent. Furthermore, the intakes of plant-foods and red and processed meat differ geographically. Providing a standardized scoring system enables more direct comparison between study populations despite the diversity of exposures.”

More to come

This is a first step, the authors note. There are clear questions that they plan to explore in additional methodological work. For example, in this initial paper, equal weight was given to each of the eight Cancer Prevention Recommendations that were included in the score. That provides a simple scoring system but it does not address the relative contribution of each recommendation to cancer risk.

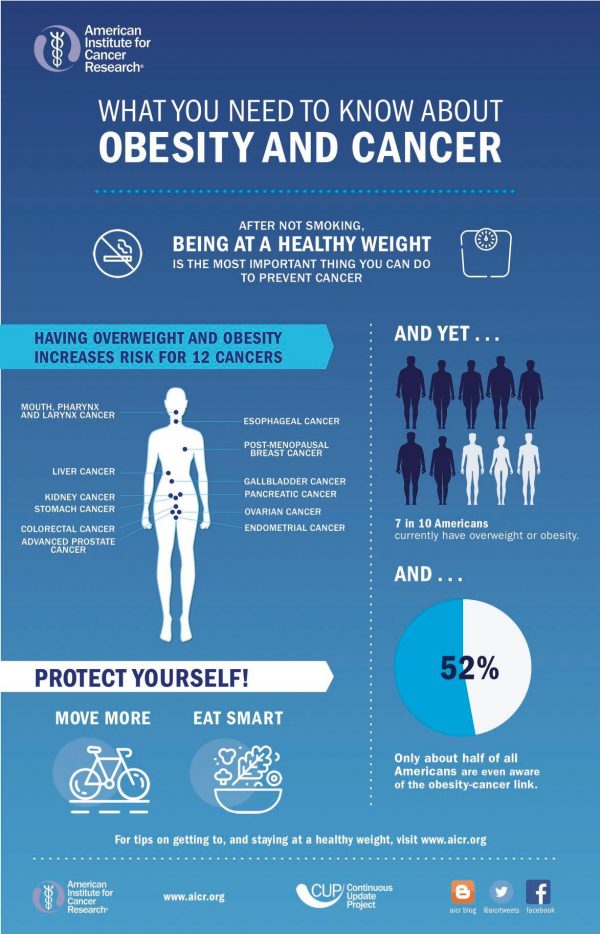

“We know that obesity increases the risk of at least 12 types of cancer and is a stronger risk factor for cancer overall than consumption of red/processed meat for cancer, which increases the risk of colorectal cancer. However, the simple unweighted scoring system gives one point for each,” said Brockton. The implications of re-weighting the components in different scenarios, such as within components, between components, and between lifestyle factors, will be reviewed in future papers.

More discussion in this area is welcome. The goal now is that researchers in different countries use this tool as a template, adapt as needed, and document any needed modifications. “I think it will be really exciting to see similar questions in different countries with different outcomes then to be able to compare them,” said Reedy.

AICR estimates that about 40 percent of all cancer cases are linked to modifiable risk factors. Maintaining a healthy weight and not smoking, along with eating a healthy diet and being physically active are all evidence-based ways to reduce cancer risk.